Sales Tax Is Calculated Brainly

Taxation is, by and large, the well-nigh important source of government revenue in well-nigh all countries. According to the most contempo estimates from the International Center for Taxation and Development, full tax revenues business relationship for more than fourscore% of total regime revenue in about half of the countries in the earth – and more than than 50% in almost every country.

We begin this entry by providing an overview of historical changes in taxation patterns, and and then move on to an analysis of available data from the last couple of decades, discussing contempo trends and patterns in taxation effectually the globe.

From a historical perspective, the growth of governments and the extent to which they are able to collect revenues from their citizens, is a striking economic characteristic of the last ii centuries. The bachelor long-run data shows that in the process of development, states have increased the levels of taxation, while at the same fourth dimension changing the patterns of taxation, mainly by providing an increasing emphasis on broader taxation bases.

Taxation patterns around the world today reveal big cantankerous-country differences, specially between developed and developing countries. In particular, adult countries today collect a much larger share of their national output in taxes than do developing countries; and they tend to rely more on income taxation to practise so. Developing countries, in contrast, rely more than heavily on trade taxes, every bit well as taxes on consumption.

Moreover, the information shows that adult countries actually collect much higher tax acquirement than developing countries despite comparable statutory taxation rates, even afterward controlling for underlying differences in economical activity. This suggests that cross-country heterogeneity in fiscal capacity is largely determined by differences in compliance and efficiency of tax collection mechanisms. Both of these factors seem to exist affected past the force of political institutions.

In the terminal role of this entry we provide an overview of empirical evidence regarding the equity and efficiency implications of tax. In particular, we show that taxation does take a powerful redistributive consequence, simply it is important to consider how taxation as well affects behavior of individuals, by changing economic incentives. For example, recent studies take found that tax may lead to efficiency losses by inducing migration of 'super stars'. These potential efficiency losses highlight the importance of designing taxation systems that achieve redistributive objectives at the smallest possible toll.

All our interactive charts on Revenue enhancement

History of tax

Taxes started growing in early-industrialised countries after the Kickoff World State of war

The visualization shows the evolution of tax revenues, as a share of national income, for a selection of early-industrialized countries.

As we can see, until 1920 tax revenues were depression across all these countries. Indeed, until 1910 less than 10% of national income was collected by these governments through revenue enhancement – just enough for them to fulfil basic functions, such as maintaining order and enforcing belongings rights.

Afterward the First Globe War, however, taxation started growing considerably. In the period 1920-1980 taxation as a share of national income increased drastically, more than doubling across all countries in the chart. These increases in revenue enhancement went together with more regime expenditure on public services, specially pedagogy and healthcare.

After 1980, revenue enhancement revenues started stabilizing, admitting with marked differences in levels for each country. Today these differences remain pregnant.

Income revenue enhancement played a fundamental function in the historical expansion of revenue enhancement revenues

The growth of tax revenues that took place in early-industrialized countries after the First Globe War was largely supported by the extension of income taxes. This required states to build tax administration systems, and implement taxation withholding at source, in society to effectively raise compliance.

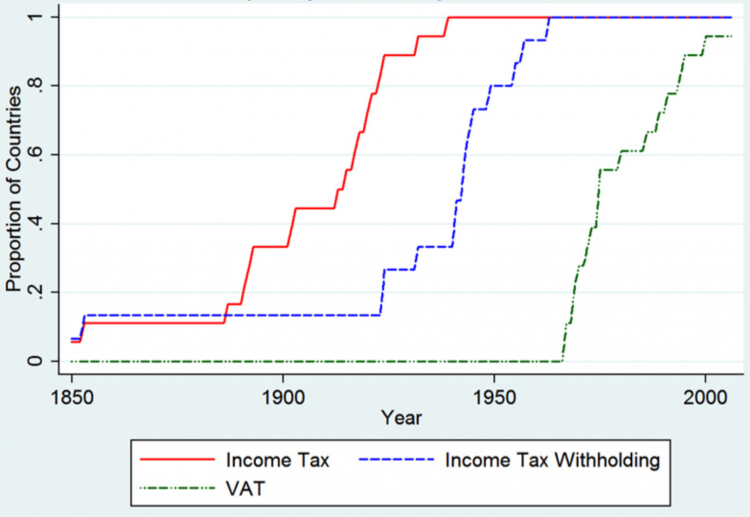

The visualization from Besley and Persson (2013)1 tracks a grouping of 18 countries, in order to show how dissimilar tax instruments became increasingly more common during the 20th century.

The vertical axis shows the relative frequency of taxation instruments within the sample of countries, and the horizontal axis shows time.2 The red line plots the share of countries with income revenue enhancement, the blue line plots the share with income-tax withholding, and the greenish line plots the share with value added taxation.

Every bit we tin can see, income taxes began appearing around 1850, with direct withholding following about 25 years later; and VAT again somewhat later. Past 1950 all countries in the sample had already both income revenue enhancement and direct withholding.

In this interactive nautical chart y'all tin see in detail how VAT, specifically, has spread effectually the world in the last few decades.

Evolution of fiscal capacity in a sample of 18 countries – Figure 4 in Besley and Persson (2013)3

In the 20th century, European countries expanded revenues from directly taxation faster than other sources of regime acquirement

As pointed out above, early-industrialized countries increase tax revenues after the First Globe State of war specifically by increasing direct forms of taxation. Here we provide farther evidence of this, and show how the taxation of incomes became increasingly important to collect revenues in these countries, also in relation to other sources of revenue.

The graph shows the proportion of total government revenue that is accounted for by income taxation. The data plotted corresponds to historical estimates from Flora (1983)4 up until 1975, and more contempo estimates, starting 1980, from the International Centre for Tax and Evolution.

As we can encounter, the relative importance of income tax inside government budgets fluctuates with time, merely there is a clear positive trend in almost cases.

Revenue structure and government structure in the US are historically interdependent

The feel of government expansion in the Usa shows that there is a link between taxation revenues, and government structure more generally.

Every bit Wallis (2000)5 points outs, in the final two centuries the US has passed through three distinct systems of regime finance. In the get-go financial system, lasting from 1790 until nearly 1842, state governments played an important office in raising regime revenue, mainly by generating 'asset income' through activities such as the sale of land. In the second fiscal organization, starting around 1840, local governments became more than important, contributing an increasing share of regime revenue from property taxes. And in the third arrangement, starting with the Smashing Depression, the federal government became more of import, generating increasingly larger revenues through the collection of income taxes.

The visualization shows how this transition took place. It provides details regarding the development of government revenues by level of government, expressed equally a share of national income – here Gross National Product (GNP).

As can exist seen in the chart, the implementation of new forms of revenue enhancement during the 20th century in the Usa, was associated with underlying changes in the structure of the regime. By clicking on the option labelled 'Relative', you can encounter how the share of national revenues rose sharply after the 2d World State of war. This is when income taxation revenues started expanding.

In the process of evolution, eye income countries accept increased tax revenues

The show that we have discussed so far is mainly from high income countries. However, the available long-run data from Latin America suggests that middle income countries have also expanded tax revenues in the procedure of evolution – admitting later, and with some differences in the relative importance of specific tax instruments.

The visualization, using data from Arroyo-Abad and Lindert (2016)six, shows the composition of tax revenues for Republic of colombia. These estimates represent to central authorities revenues, and are expressed as a share of national income – specifically Gross domestic product. Comparable data, from the same source, is also bachelor for Republic of peru; you lot tin can come across the corresponding figures by clicking on the option labelled 'Change'.

Equally we can see, revenue enhancement revenues started growing noticeably in the 1960s, mainly through the collection of consumption taxes. Past clicking on the option labelled 'Relative', you can see the relative importance of the different tax instruments. As it can be appreciated, income tax became an of import source of revenue in the 2nd half of the 20th century, although consumption tax grew faster than income revenue enhancement throughout this period.

Taxation today

What are the main instruments used by governments to collect revenue?

In the preceding section we discussed the historical evolution of government revenues, and provided evidence of the of import role that taxes, specifically, played in the expansion of governments. Simply what is the full menu of instruments that governments have to collect revenues?

Roughly speaking, governments finance policy from taxes, grants (typically in the form of 'development assistance' transfers), and debt (more precisely upkeep deficits, or reductions of budget surpluses).

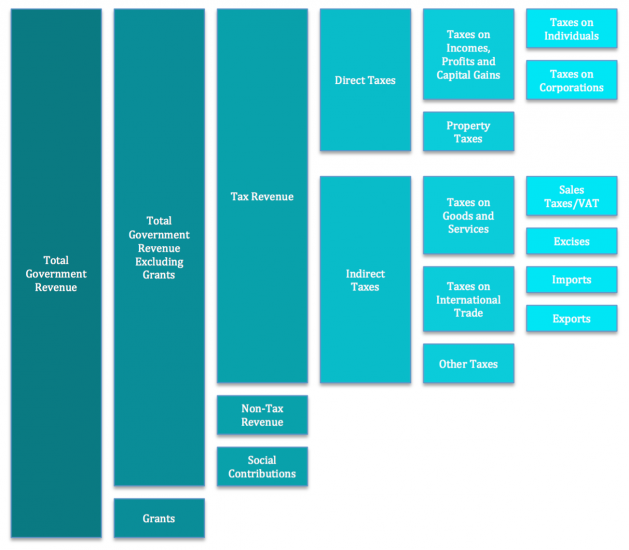

The diagram, from Prichard et al. (2014)7, provides a conceptual classification of revenues other than debt.

As nosotros can meet, these revenues include grants, straight taxes (such every bit taxes on income, profits, holding, etc.), indirect taxes (such every bit taxes on consumption, sales, trade, etc.), and social contributions.

Classification of unlike sources of government revenues – Effigy 2 in Prichard et al. (2014)eight

How much tax acquirement do countries collect today?

The visualization shows a map of full tax revenues. These estimates comes from the International Centre for Taxation and Development, and are expressed equally a share of GDP.

As we tin see from the nigh recent data, at one extreme of the spectrum nosotros take countries such every bit Cuba, France, Denmark, Norway and Sweden, where total tax revenues are higher than 30%. And at the other extreme, we have countries such as Great socialist people's libyan arab jamahiriya and Kingdom of saudi arabia, where taxes account for less than two% of national income.

More generally, this map shows that there is a articulate correlation between GDP and revenue enhancement revenues – richer countries tend to collect through taxes a much larger share of their domestic production. This is a remark that we accost in more than detail in the post-obit sections.

The visualisation uses the same data, but plots the evolution of tax revenues for individual countries. You can add countries past clicking on the option ' Add land '; and you can switch between the 'map' and 'chart' views by clicking on the tabs at the top of the graph.

The fourth dimension serial show that near high income countries take had relatively stable levels of tax revenues in the last decade; while trends and patterns are less clear beyond the developing world. In many cases, peculiarly among upper-center income countries, revenue enhancement revenues take been going up consistently. The case of Turkey stands out: in 1980 it collected almost 13.5% of GDP in taxes (well-nigh one-half of the US), still by 2001 it had almost doubled tax revenues – near catching upwards with the U.s..

In any case, despite specific cases such every bit Turkey, differences today remain large and there is no clear evidence of global convergence. In many developing countries levels are very depression and trends have not been persistently going upwards by a significant margin.

How practise developing and developed countries compare in terms of revenue enhancement revenue?

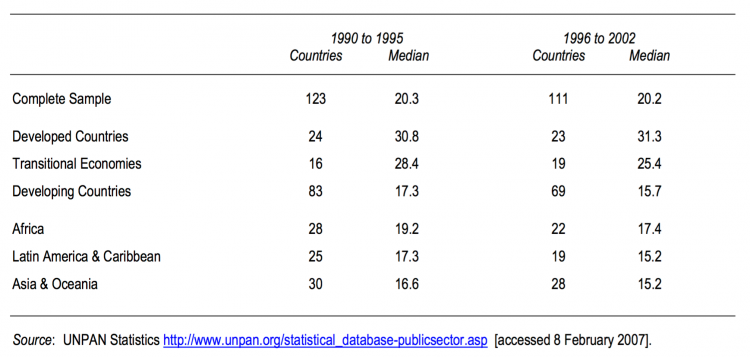

The table, from Jha (2008)9, shows differences in tax revenues equally a share of Gross domestic product for diverse country groups. The tabular array pools countries within groups, across 2 periods of time: 1990-1995 and 1996-2002. For each time-group pool of countries, the author ranks countries by tax acquirement as share of national income, and reports the level for the country in the middle (i.e. the median tax revenue within that time-group pool). This gives us an idea of the 'typical' country in that region, at that point in fourth dimension.

As we tin come across, developed countries collect well-nigh twice as much as developing countries in tax revenue. And developing countries, in turn, collect almost one-half equally much as transition economies. Also, we can see that adult countries had little change in revenue enhancement-to-Gross domestic product ratios in the 2d half of the 20th century, where as in developing countries in that location seems to be a wide negative tendency.

Cardinal Government Tax Acquirement every bit a Pct of Gdp, 1990–1995 and 1996–2002 – Tabular array 1 in Jha (2008)10

Which forms of taxation dominate revenues in dissimilar world regions?

We take already discussed the fact that levels of taxation differ greatly beyond world regions – both in levels and trends. Now we focus on differences in the composition of revenue enhancement revenues.

The visualization presents a breakup of tax revenue sources, comparing figures from 1986 and 1996. The estimates are provided for a selection of country groups (you can switch country groups by clicking on the option 'change country group'), and are expressed every bit a share of Gdp. The data comes from Todaro and Smith (2014)11, and includes directly taxes (corporate and income taxes), as well as indirect taxes (general, commodity and excise taxes) and social security contributions.

Although these estimates are somewhat dated, they do provide a rough idea of taxation patterns by world regions. As it can be seen, developing countries depend significantly on indirect taxes, particularly taxes on trade and consumption. This can exist contrasted with the case of OECD countries, where direct tax – peculiarly personal income tax – is comparatively more important.

It is as well worth noting the important function of social security revenues in advanced economies: at 10% of Gross domestic product in 1996, social security revenues are almost 10 times larger than in developing countries.

More recent data suggests that direct revenue enhancement, and specifically income taxation, remains more important in developed countries than in developing countries. The visualization plots total acquirement from taxes on income and profits (horizontal axis) against revenue from taxes on goods and services (vertical axis). Estimates comes from the International Heart for Tax and Development and are expressed every bit share of Gross domestic product.

Every bit we can meet, there is a positive correlation on the amass, and European countries are consistently located further towards the pinnacle right.

It tin can also be checked that almost countries in the OECD are shut, or below a hypothetical line with gradient equal to i (i.e. feature higher income tax revenues than commodity revenue enhancement revenues); Denmark is an extreme case, with income tax revenues more than doubling receipts from taxes levied on appurtenances and services.

Taxation of incomes

How accept income taxation revenues evolved around the world?

The visualization provides an overview of revenues from income taxation (specifically taxes on incomes, profits and capital letter gains) during the period 1980-2017. The estimates correspond to direct tax of individuals and corporations, and are expressed as share of Gdp. A selection of countries is included past default, but you tin can add more countries by clicking the ' Add together country ' option.

The data shows large and persistent cross-state heterogeneity, fifty-fifty inside relatively similar countries, such as those in the OECD.

In comparison to developing countries, the data too shows that in developed countries the direct taxation of corporations and individuals accounts for a larger share of national production. And this has been consistently the case throughout the last couple of decades.

Every bit noted before, an important function of regime revenue in developed countries comes from direct forms of taxation, so information technology is non surprising that the evolution of income tax tracks closely the stable evolution of taxation revenues that we discuss above.

Some specific countries are peculiarly interesting. In Prc, for example, the share of GDP that is collected past taxing individuals and corporations almost doubled in the menstruum 2000-2012.

Marginal income revenue enhancement rates from a historical perspective

One of import feature of income revenue enhancement systems is the statutory rate of taxation that applies to the highest bracket of incomes. This mensurate, usually known equally the 'tiptop marginal rate of taxation', corresponds to the taxation rate that applies to the 'last dollar' of income earned past the rich.

The chart here gives united states an idea of how income taxation has inverse in rich countries, past plotting trends in acme marginal rates beyond French republic, Germany, the Us and the United kingdom, for the menses 1900-2013.

As we can see, at the turn of the 20th century the elevation earners in these countries faced almost zippo taxation on the last function of their incomes; but this inverse drastically effectually 1910-1930, when high top marginal rates were introduced. Interestingly, however, this lasted only until almost 1980, when again all countries essentially reduced rates. Today the levels are between one-half and a tertiary of what they used to be at the highest point. In the Uk, in 1978 the last pound of earned income at the highest bracket was essentially entirely taxed (98%). Today the corresponding figure is less than half (45%).

How accept statutory tax rates for the rich evolved in the last few decades?

The chart here shows the sharp trend of reducing top marginal revenue enhancement rates after the 1980s, as a global phenomenon expanding both adult and developing countries.

The estimation of this graph oftentimes leads to defoliation. A common error is to interpret the tiptop marginal tax charge per unit as the constructive rate of tax applied to the rich. This is incorrect, considering the top marginal rate applies (as the 'marginal' proper noun suggests) only to the last portion of income earned by the rich. And by implication, lower marginal rates do not directly imply lower economical incidence of taxation for the rich.

Having said that, additional evidence does seem to propose that the reduction of pinnacle marginal income taxation rates has been 1 of the ingredients contributing to lower effective tax rates for the rich. Nosotros talk over this additional evidence in the side by side section.

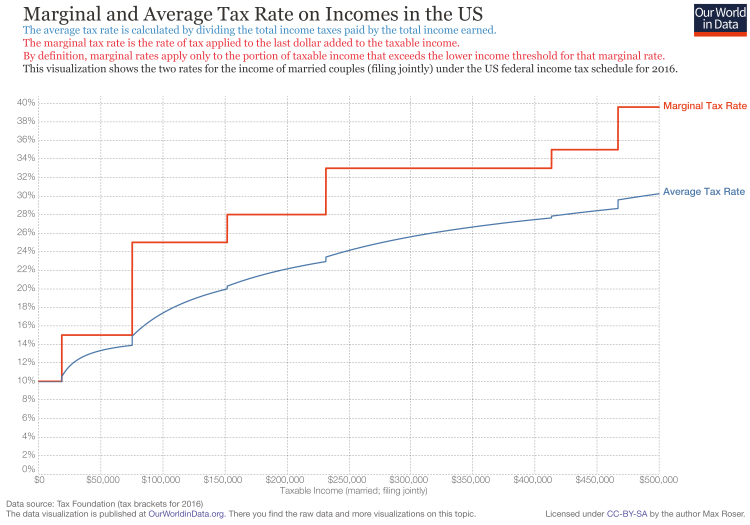

How do marginal rates of taxation compare to average rates of taxation?

The marginal rate of taxation is defined every bit the rate of tax that is applied to the 'last dollar' added to the taxable income. This means that marginal rates apply only to the portion of taxable income that exceeds the lower income threshold for that marginal rate.

In contrast, the average, or effective rate of revenue enhancement is divers equally the ratio of full taxes paid by total income earned – that is, the share of income that is paid in income taxes.

The distinction between these two concepts is important because for many people, a portion of their income is taxed at one rate, and the rest is taxed at another charge per unit. In the US, for example, if a married couple earns $40,000 a twelvemonth, they pay federal income taxes at a rate of x% on the first $18,500 or so, and at a charge per unit of 15% on the rest. Hence, while the marginal rate applied to the final dollar earned is 15%, the effective income revenue enhancement rate is lower.

Using the US federal income tax schedule, the visualization shows the marginal and average rates for the income of married couples (filing jointly). These figures use estimated tax brackets for 2016 from the Tax Foundation.

This visualization shows that boilerplate and marginal income revenue enhancement rates are clearly unlike. Specifically, while both average and marginal rates are increasing, boilerplate rates are smoother and generally lower.

A similar chart showing marginal and average rates for the income of single individuals – equally opposed to married couples filing jointly – can be found here.

Marginal and average tax rate on incomes in the US – Our Earth in Information, with 2016 estimates from the Tax Foundation

Revenue enhancement of consumption

How is consumption taxed?

We have already outlined higher up the chief instruments used past governments to collect acquirement. Hither we want to provide more detail regarding different forms of 'commodity taxation', in particular consumption taxes.

In the OECD nomenclature, consumption taxes (taxes on product, sale, transfer, leasing and delivery of goods and rendering of services) include two sub-categories: general taxes on goods and services (taxes on general consumption including VAT, sales taxes and other general taxes on goods and services) as well as taxes on specific goods and services consisting primarily of excise taxes (also as community and import duties and taxes on specific services, such equally taxes on insurance premiums and fiscal services). For more details come across OECD (2016).12

The key distinction between VAT and excise taxes is that VAT is paid by consumers, while excise taxes are paid past producers. In other words, they take a different statutory burden. As we talk over below, the statutory burden of a tax does not necessarily describe who really bears the economic burden of the tax.

How has the taxation of appurtenances and services evolved around the world?

The visualization provides an overview of revenues from the taxation of goods and services during the period 1980-2017. The estimates account for sales taxes, value added taxes and excise duties; and are expressed as a share of Gdp.

The data shows some cross-land heterogeneity; although relative to acquirement from income taxation, heterogeneity in commodity taxation is much smaller, specially among loftier-income countries.

Equally can be seen, most of the countries with particularly low taxation-to-GDP ratios are in Africa.

How important are different forms of article tax in OECD countries?

We accept already noted that taxes on goods and services tend to be less important in loftier-income countries than in low-income countries. Here we want to focus on the relative importance of different forms of commodity taxation.

The visualization plots the evolution of VAT and excise taxes in the OECD. The figures correspond to OECD averages and all values are expressed as percentage of total taxation. These figures give usa an idea of the evolution of the importance of different forms of commodity taxation in OECD countries.

As we can see, the limerick of consumption taxes has fundamentally changed in the OECD over the last few decades: the weight of consumption taxes has been stable, because the substantially increased importance of VAT has been effectively balanced by a reduction in importance of other taxes on specific appurtenances and services, the majority of which are excise taxes.

How do statutory consumption revenue enhancement rates compare across countries?

The visualization shows how value added tax rates compare between world regions. These figures come from the World Development Report (2005), and include corporate tax rates every bit a benchmark.

This visualization shows that value added tax rates are similar in developed and developing countries, which suggests that the differences we observe in revenue between regions, are likely due to differences in compliance. In fact, this is non only specific to article tax – Besley and Persson (2013)13 show that developed countries tend to raise much more income-tax revenue than developing countries with comparable statutory rates, which suggests that the taxation base in low-income countries is more strongly affected by compliance difficulties.

In summary, the show suggests that fiscal chapters (i.e. the extent to which countries tin extract revenues through taxation at any given level of economic activity) is considerably less developed in poor countries.

How mutual are VAT exceptions?

Most VAT systems effectually the globe adopt multi-rate systems with one or more than reduced rates applying to item goods. The nautical chart, from OECD-KIPF (2014),14 shows the goods and services that are most commonly subject area to reduced VAT rates in OECD countries.

As can be seen, in well-nigh countries that use VAT exceptions, reduced rates tend to apply to basic products in which low-income households spend a larger share of their income (such equally food); as well as to products with perceived positive social spillovers (such as newspapers, books and medicines).

Many countries also use reduced rates for other reasons. From this chart, it seems similar providing support to specific industries, such as tourism, is another important gene considered by governments.

Common reduced VAT rates in OECD countries (as at 1 January 2014) – OECD-KIPF (2014)15

Contempo trends in the incidence of revenue enhancement

Taxes touch on market prices, so the statutory burden of a tax does not describe who really bears the tax

Taxes affect economic interactions by changing the relative prices of goods and services in the economy. This implies that, to assess who bears the burden of a tax, information technology is non sufficient to look at statutory revenue enhancement rates. For example, if a tax is imposed on producers, in a competitive marketplace they will enhance prices to some extent to offset this taxation brunt – so the producers' income will not fall past the full amount of the taxation. A similar statement can be fabricated if the taxation is levied on consumers, since in a market economy the tax will lower demand, and this will have a outcome also for producers.

The key point is that, in order to analyze the economic incidence of tax in a marketplace economy, we need to look beyond statutory tax rates. Below we provide concrete examples of how economists try to estimate the economic incidence of taxation.

How much taxes do rich households pay in the US?

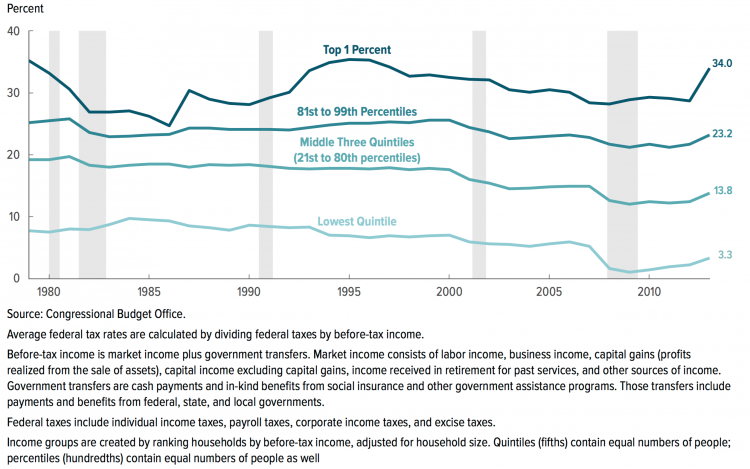

In the Usa, the Congressional Budget Part (CBO) produces estimates of the incidence of tax across the population. To practise this, they make the post-obit assumptions: (i) Taxes on earnings are borne by workers; (ii) Taxes on individual income are borne past the households that pay them; (iii) Taxes on corporate income are borne by individuals in proportion to their capital income; (iv) Taxes on consumption are borne by individuals in proportion to their consumption.16

Based on these assumptions, the CBO calculates total tax contributions every bit a share of pre-tax income for dissimilar segments of the pre-tax income distribution.17 These estimates, frequently referred to as 'average tax rates', tin be interpreted as the effective rates of taxation that utilise to individuals with different incomes, afterward accounting for government transfers (specifically cash payments and in-kind benefits from social insurance and other government assistance programs).

The visualization, plotting CBO estimates of average tax rates, shows that the federal tax system in the U.s. has been generally progressive: those located higher in the ranking of incomes, pay a higher share of their income in taxes.

Beyond time, we can also see that progressivity has not been constant – the period 1980-1990 saw important reductions in tax rates for the rich, without comparable reductions for the poor.

The hike in revenue enhancement rates towards the cease corresponds primarily to pregnant changes in tax rules in 2012. Up until that point, and since effectually 1995, revenue enhancement rates for the richest ane% went downwards every year (although they also went down for the lower income groups in the aforementioned menstruation).

Average federal revenue enhancement rates, by earlier-tax income Group, 1979 to 2013 – Effigy 2 in CBO (2016)18

How progressive is taxation at the top of the income distribution in developed countries?

The visualization higher up shows that, according to the estimates from the Congressional Budget Part, richer individuals in the US generally tend to conduct a larger burden of taxation than the poor. Hither we examine whether this is also true inside the top of the income distribution – that is, whether the 'ultra rich' shoulder a larger taxation burden than the 'rich'.

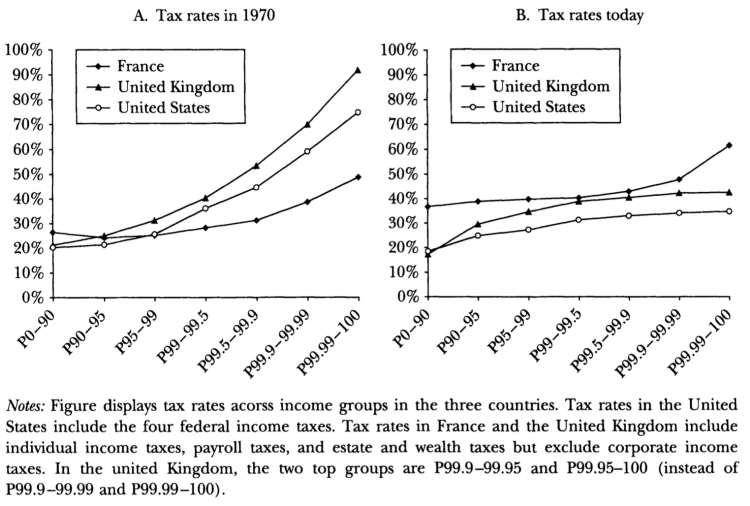

The next visualisation, from Piketty and Saez (2007)nineteen shows estimated average tax rates in France, the U.s. and the United kingdom, at two points in time: 1970 and 2005. Notice that these are boilerplate rates (i.due east. total revenue enhancement contributions as a share of pre-tax income), which are unlike to marginal tax rates.

Displayed are rates for the bottom 90% of the income distribution, as well equally college percentiles. Again, we can see in these estimates that the systems in question are progressive – increasingly college percentiles in the income distribution pay increasingly higher constructive rates of taxation. However, the lines are much flatter in 2005, which shows that the systems have become less progressive at the top: the average share of income paid by those at the very superlative of the income distribution has dropped substantially since 1970. This is important because, equally the authors of the effigy point out, over the same period pre-tax income inequality grew significantly: a few very rich individuals at the very tiptop are accumulating an increasingly large share of national incomes.

An important indicate that should be kept in mind is that these estimates are not directly comparable to those from the Congressional Budget Office discussed above, because they practice non take into business relationship regime transfers, and rely on different methodological assumptions – for example, they do not consider excise taxes (but they do consider estate taxes). For more details come across Piketty and Saez (2007).

Boilerplate tax rates by income groups in French republic, the U.k., and the Usa, 1970 and 2005 – Figure 4 in Piketty and Saez (2007)xx

The drivers of revenue enhancement revenues

Rising Gdp is associated with ascension taxation revenues

We have already pointed out that rich countries tend to collect much higher tax revenues than poor countries. The visualization provides further evidence of the extent of this correlation.

The vertical axis measures GDP per capita (after accounting for differences in purchasing ability across countries), while the horizontal axis measures tax revenues as share of GDP. The vertical axis is expressed past default in a logarithmic calibration, so that the correlation is easier to capeesh – you lot can change to a linear scale by clicking the 'Log' button.

We can see that there is a strong positive correlation: richer countries tend to have higher tax revenues as a share of their GDP. And this is likewise true within globe regions (represented here with different colors).

Early-industrialized countries became improve at collecting revenue every bit they developed

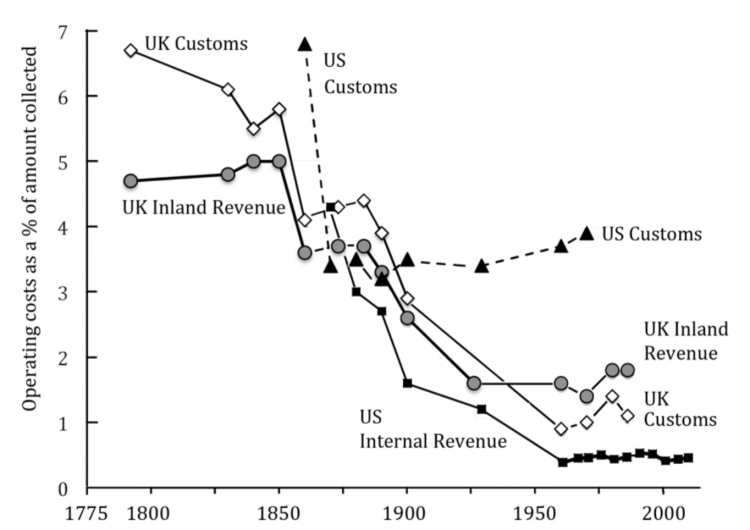

We argued above that the efficiency of tax collection is a strong predictor of cross-state differences in tax revenues – rich countries take more than capacity to extract revenues. As historical data shows, this capacity was largely possible considering, throughout the 19th century and up until the starting time half of the 20th century, these countries found increasingly cheaper means to collect taxes.

The visualization, from Lindert (2012)21, shows that the U.s.a. and the UK saw steep declines in the administrative cost shares of indirect tax collection across the 19th century and the early 20th. Equally we can see, the cost of collections dropped, from over 4.5% of the amounts collected in the mid-19th century, to 2% since the middle of the 20th century.

Tax drove costs as a percentage of the amount collected by central governments, The states and U.k., 1787/96-2011 – Figure ii in Lindert (2012)22

Taxation collection relates to the strength of political institutions

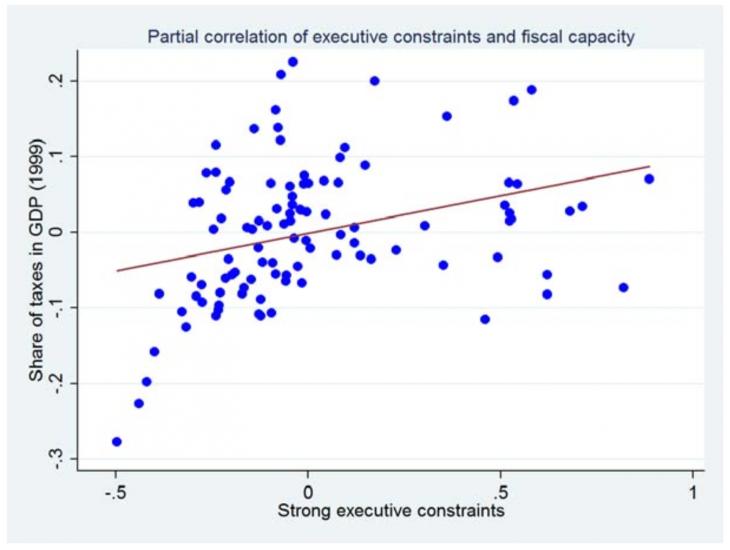

Cantankerous-country differences in tax revenues are linked to the chapters of countries to implement efficient tax collection systems. Hither we provide evidence suggesting that political factors – such every bit the extent of institutionalized constraints on the conclusion-making powers of policy makers – help shape the level and evolution of fiscal capacity of countries.

The chart, from Besley and Persson (2013)23, plots the cantankerous-state relationship between political institutions and tax revenues. The authors approximate the strength of political institutions by calculating the proportion of years since independence (or since 1800 if independence is earlier) that a country had strong constraints on the executive. Having 'stiff constraints on the executive', in turn, is measured from the well-known Polity Four information base of operations (you tin can read nigh measurement and definitions in the Polity Iv dataset users' transmission). In essence, this variable aims to capture the extent to which accountability groups impose institutionalized constraints on the controlling powers of policy makers.

The besprinkle plot controls for baseline differences in GDP – that is, what we observe is the correlation between tax revenues and political institutions conditional on Gdp levels. As nosotros can run into, countries with strong executive constraints collect higher tax revenues, when income per capita is held constant, than practise countries with weak executive constraints.

Some studies advise that, under weak accountability, countries may not but have generally weak taxation systems, simply may also be subject area to 'political budget cycles' whereby tax collection declines prior to elections, as politicians seek to secure curt-term political support (See Prichard 201624 and the references therein for more details).

Tax acquirement vs constraints on executive authority

Aid correlates negatively with tax revenue, merely the link does non seem to exist causal

A large body of academic literature has studied the relationship between acquirement from development aid ('strange aid') and revenue from taxation. The hypothesis supporting this strand of literature is straightforward: foreign assistance may 'oversupply out' domestic revenue enhancement revenues, as information technology reduces the incentives for policy-makers to pursue politically plush tax collection.

This hypothesis seems to be supported by raw correlations. The plot, from Benedek et al. (2014)25, shows the evolution of tax revenues and foreign aid (Overseas Development Assist – ODA). Information technology shows a broad negative association: between 1980 and 1995, when strange aid as a share of GDP was increasing, average tax revenue in relation to GDP decreased slightly. Mail service-1995, a decline in the share of full cyberspace ODA to Gdp was accompanied by college tax revenues every bit per centum of GDP.

This relationship cannot be interpreted causally, every bit at that place are many factors that simultaneously drive ODA flows and tax revenues. More complex econometric studies that try to account for further sources of bias notice that in that location is no consistently pregnant relationship between assist and tax drove (see Prichard 201626 and the references therein for more details).

Average cyberspace development assistance and taxation revenue in low and middle income countries, 1980–2009 – Figure 1 in Benedek et al. (2014)27

The consequences of taxation

Taxation is an important musical instrument to reduce inequality

One way to gauge the extent to which taxation redistributes resources between individuals in a country, is past looking at how the distributions of incomes change before and after taxes. The visualization does this, showing the reduction of inequality that dissimilar OECD countries attain through taxes and transfers.

The estimates represent to the percent point reduction in inequality, every bit measured by changes in the Gini coefficients of income, before and after taxes and transfers. The source for the data is the 2016 OECD Inequality Update as part of the OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD) November 2016 Release: Income inequality remains high in the face up of weak recovery. The IDD provides further details regarding how these estimates are synthetic. In a nutshell, income 'before taxes' corresponds to what is ordinarily known as marketplace income (wages and salaries, self-employment income, capital letter and property income); while income after taxes and transfers corresponds to disposable income (market income, plus social security, greenbacks transfers and individual transfers, minus income taxes).

The data shows that across the 35 countries covered, taxes and transfers lower income inequality past around 1-third on boilerplate (equivalent to around 0.15 Gini points). However cross-country differences are substantial, with declines ranging from about twoscore% in Kingdom of denmark and Ireland, to about 8% in South Korea. The U.s. – a country with high baseline levels of inequality – achieves a reduction of effectually 17%, which is a piffling over half of the OECD average.

Mostly speaking, countries that accomplish the largest redistribution through taxes and transfers tend to exist those with the lowest later on-tax inequality.

While informative for the purpose of cross-country comparisons, these results accept to exist interpreted carefully, since the before-tax distribution of incomes is already the result of choices fabricated by individuals who take taxes and transfers into consideration. Put but, the before-tax distributions of incomes are likely to be different to the bodily distributions of incomes that would be in place if at that place were no taxes or transfers. This can exist clearly explained in the context of pensions: individuals receiving state pensions appear in the data as poor earlier transfers; but many of them would of course accept private pensions if they lived in a country without state transfers.

The extent to which taxes bear upon behavior is discussed in more detail below.

Revenue enhancement can atomic number 82 to efficiency losses

In market economies, consumers and producers alter their beliefs in response to taxes. For example, if a taxed practiced has a substitute that is not taxed, some consumers will shift to the substitute to avoid the tax. These changes in behavior can pb to inefficiencies. For case, high tax rates may discourage labor supply; and in the example of very rich individuals, they may even induce migration of talent to countries where the tax burden is lower. In both cases, the 'size of the pie' would be reduced past revenue enhancement. So how large are these behavioral responses?

Using data from the European football marketplace, Kleven et al (2013)28 find show of strong mobility responses to taxation for 'superstars'. The scatterplots support this.

The two plots correspond to different time periods. The vertical axis represents the fraction of all pinnacle-league professional football players who are foreign nationals in the country where they play, and the horizontal centrality shows the average superlative earnings revenue enhancement rate for foreign players in that country.

Equally we tin can see, in the menstruation 1985-1995 in that location was no correlation between migration and revenue enhancement rates; notwithstanding in the flow 1996-2008, later the Bosman ruling on gratuitous mobility was enacted, the correlation became strongly negative: the countries with higher elevation earnings tax rates became less likely to have foreign players.29

The authors also show that the mobility of players had a negative impact on the performance of football game clubs of countries with high taxation rates.

This testify, suggesting that 'superstars' are very responsive to tax, contrasts with the available show for typical individuals – while still highly debated, about empirical estimates suggest that for the majority of the population, labor supply choices are not very responsive to changes in income tax rates (see Saez et al. 201230 for a review of the literature).

Cross-country correlation between tax rates and migration of football players – Figure i in Kleven et al (2013)31

Definitions & Measurement

The almost widely used global data source on tax is the International monetary fund Government Finance Statistics (GFS) . This is the source used to produce the Globe Development Indicators from the World Bank, and is an input for the production of many other related, but different sources of information, including (i) the OECD Revenue enhancement Statistics dataset; (ii) the OECD Revenue Statistics in Latin America dataset; and (iii) the CEPALSTAT Revenue Statistics in Latin America database

Combining data from all these sources, the International Center for Tax and Evolution (ICTD) produces the ICTD Authorities Revenue Dataset.

The data produced past the International monetary fund, the Earth Bank, the OECD and CEPAL often covers unlike countries at dissimilar points in time; and for those years and countries in which estimates overlap, at that place are significant inconsistencies.

The inconsistencies between sources are oftentimes due to differences in methodological choices – such as differences in the classification of social security contributions, or the omission of data from taxes nerveless by local governments. And in addition to methodological differences, sources besides seem to differ in other substantial non-systematic means. A very detailed business relationship of data quality differences can exist found in Prichard et al. (2014).32

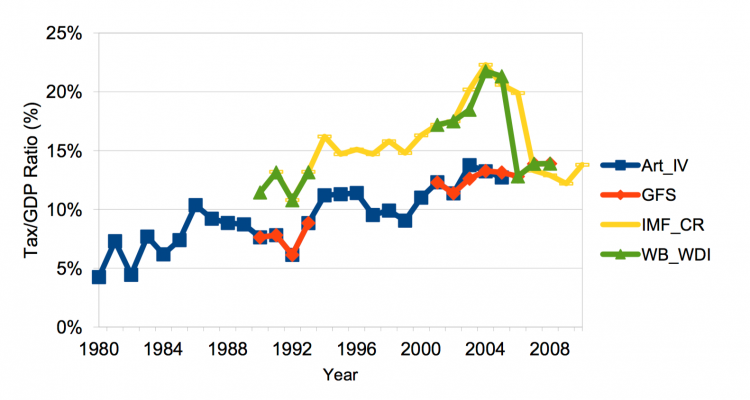

The chart shows an example of information discrepancies in tax revenues for Ghana. The different series stand for to different sources: the blueish line denotes estimates using IMF Commodity IV reports, the orange line denotes estimates from the International monetary fund Authorities Finance Statistics, the yellow line denotes data from IMF Country Reports, and the green line denotes estimates from the World Depository financial institution Earth Development Indicators.

Considering the above data limitations, the ICTD developed the new Government Revenue Dataset, merging and prioritizing sources under a standard classification system. Prichard et al. (2014)34 provide a detailed account of the information limitations identified by the ICTD, and how they tried to accost them in the new ICTD Government Acquirement Dataset.

Alternative measures of Tax revenue (% Gdp), Ghana, 1980-2010 – Figure 2 in Prichard 201633

Data Sources

Historical cross-country series

Flora et al. (1983)

- Data Source: Flora, Peter et al. 1983. State, Economic system and Guild in Western Europe, 1815-1975. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag

- Description of available measures: Taxation revenues by source

- Time span: 1815-1975

- Geographical coverage: Western Europe

- Link: http://gpih.ucdavis.edu

Piketty (2014)

- Data Source: Piketty, T. (2014). Majuscule in the 21st Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- Description of available measures: Tax revenues (share of national income) and marginal taxation rates

- Time span: Total tax revenues 1815-2008, Marginal Tax Rates 1900-2013

- Geographical coverage: Selected countries in Western Europe

- Link: http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/en/capital21c2

Approach-Abad and Lindert (2016)

- Data Source: Approach Abad, L. and P. Lindert. "Fiscal Redistribution in the Americas since the Mid-Nineteenth Century" in Latin American Inequality in the Long Run, edited by L. Bertola and J. Williamson, forthcoming.

- Description of available measures: Revenue enhancement revenues by source

- Fourth dimension span: 1901-2013

- Geographical coverage: Selected countries in Latin America

- Link: http://gpih.ucdavis.edu

Up-to-date cross-country serial

OECD.stat

- Data Source: OECD Revenue Statistics, OECD Latin American Tax Statistics

- Description of available measures: Taxes and other government revenues (share of Gross domestic product), every bit well equally selected statutory revenue enhancement rates and thresholds

- Time bridge: The longest series cover 1965-2014, only many countries have significantly shorter series

- Geographical coverage: OECD member countries and other selected countries from Africa, Asia and Latin America

- Link: http://stats.oecd.org/

World Banking concern Data

- Data Source: World Development Indicators and IMF Government Finance Statistics

- Description of available measures: Taxes and other government revenues (in current local currency units, as share of Gdp, and as share of government revenues)

- Fourth dimension span: The longest series cover 1970-2014, but many countries have significantly shorter series

- Geographical coverage: Global by country

- Link: https://data.worldbank.org

CEPALSTAT

- Information Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean

- Clarification of available measures: Tax revenue by type of taxes (in current local currency units and as share of Gdp), likewise every bit selected statutory tax rates

- Time span: Most series encompass 1990-2013, but some are shorter

- Geographical coverage: Latin America and the Caribbean

- Link: http://estadisticas.cepal.org

ICTD Regime Acquirement Dataset

- Information Source: International Center for Tax and Evolution, using data from OECD Revenue Statistics, OECD Latin American Revenue enhancement Statistics, International monetary fund Government Finance Statistics, International monetary fund Article Iv Staff Reports, and CEPALSTAT Acquirement Statistics in Latin America

- Description of available measures: Taxes and other government revenues (share of GDP)

- Fourth dimension span: Near series cover 1980-2013, but some are shorter

- Geographical coverage: Global by land

- Link: http://www.ictd.ac/datasets/the-ictd-government-acquirement-dataset

OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database (GRSD)

- Data Source: OECD, using data from the iv 'Revenue Statistics' publications: 'Revenue Statistics in Africa', 'Revenue Statistics in Asian and Pacific Countries', 'Acquirement Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean', and the OECD'southward 'Revenue Statistics'

- Description of bachelor measures: Taxes and other government revenues (share of Gross domestic product) to provide internationally comparable tax acquirement statistics for participating countries

- Fourth dimension span: 1990 to 2016, dependent on country

- Geographical coverage: 80 countries, set to expand to xc countries by the end of 2018

- Link: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RS_GBL

Sales Tax Is Calculated Brainly,

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/taxation

Posted by: lottwasso1969.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Sales Tax Is Calculated Brainly"

Post a Comment